Labor advocates: Most lethal state in the nation for workers ignores blue-collar plight

By Wyoming News Exchange

April 29, 2025

A backhoe operator prepares to bust and scoop up another section of sidewalk at Kelly Walsh High School in Casper. Construction worker Juan C. Avalos of Colorado died in a workplace accident at the construction site June 17, 2016. (Dustin Bleizeffer/WyoFile)

• It’s Workers Memorial Day. Yet Wyoming elected officials mostly silent in wake of yet another alarming report of workplace carnage, advocates say.

By Dustin Bleizeffer, WyoFile.com

In 2023, a worker died after falling through a skylight on a construction job. Another died after being thrown from a front-end loader. Yet another was buried in a trench collapse and two were crushed by vehicles they were either inspecting or repairing at the time, according to the Wyoming Occupational Safety and Health Administration’s fatal accident alerts website.

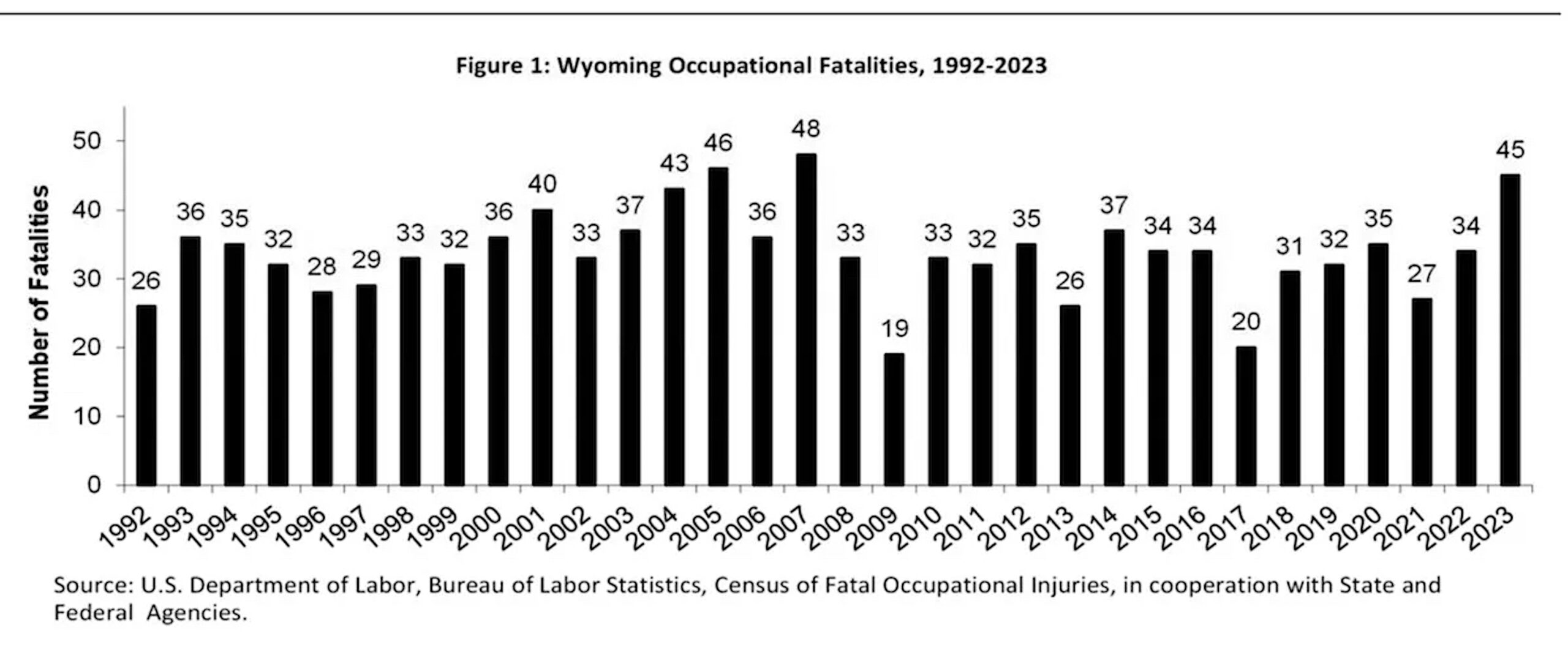

The five “alerts” — limited to two sentences or less — belie the actual extent of occupational fatalities in Wyoming that year. Forty-five workers died on the job in 2023 — a 32.4% increase over the previous year and the deadliest since 2007, according to the state’s most recent annual report on workplace fatalities.

Unless a local newsroom reports on a workplace fatality, or there’s civil litigation, most victims’ names disappear into the maw of multiple bureaucracies where extracting the type of information that might point to problem areas and potential solutions is frustratingly difficult, advocates and officials say.

“These aren’t just statistics — they’re our neighbors, family members and fellow Wyomingites,” Wyoming AFL-CIO Executive Director Marcie Kindred said in a prepared statement.

Today is Workers Memorial Day. Workers and their advocates will gather at the steps of the Capitol in Cheyenne beginning at 5:30 p.m. to commemorate the dozens of lives lost each year while on the job in Wyoming. The workplace tragedies are not only preventable but so frequent that Wyoming has ranked the worst or among the worst in the nation — on a per-capita basis — for decades, according to federal data.

The state doesn’t appear to be on track to shed its deadly distinction.

Last year was comparably deadly, though there’s no official tally yet, and at least four workers have died on the job so far this year, according to Wyoming OSHA. They include: David Wesley Moore, 58, of Douglas, killed in a natural gas compressor station fire in Converse County; Alexander Harsha, 22, of Rock Springs, hit by a door that was struck by a forklift in Sweetwater County; Liam Cobb, 19, of Casper, died by suicide, falling from a wind tower in Carbon County; and Denice Downing, 47, of Gillette, killed in a tanker-truck explosion in Campbell County.

“Year after year, we gather [on Workers Memorial Day] to honor those we’ve lost, yet we see no meaningful improvement in workplace safety,” Kindred said. “We need concrete action to protect Wyoming’s workers.”

Despite the state’s December report confirming yet another notch to Wyoming’s dishonor as the “deadliest,” it doesn’t appear that the carnage — including the hardships families face — is a priority among elected officials. Past state-level initiatives, along with some industry-led safety efforts, seem to have fallen by the wayside, advocates say. Rather than a call to action to understand how to make Wyoming workplaces safer, Kindred said, worker advocates had to fight this year to defeat a measure to reduce unemployment benefits.

Kindred said she recently told union members: “Your elected officials spent your taxpayer dollars arguing about pronouns and bathrooms. Meanwhile, we’re dying out here.”

Each year, the Wyoming AFL-CIO, along with the Wyoming Trial Lawyers Association, pleads with lawmakers to take on the worker fatality crisis as an interim topic, and each year, legislative leadership declines.

“I don’t think we value workers in Wyoming like we should,” said Wyoming Trial Lawyers Association Executive Director Marcia Shanor, who has advocated for workplace safety for decades. “If we did, we would never tolerate 45 people being killed without asking about it.”

This chart depicts occupational fatalities in Wyoming from 1992 to 2023. (Wyoming Department of Workforce Services)

What’s driving the crisis?

The 45 occupational fatalities in 2023 made Wyoming the most lethal state in the nation for workers on a per-capita basis — by a long shot.

Wyoming recorded 16 fatalities per 100,000 workers, according to the most recent federal data available. North Dakota was second at 9.8 deaths per 100,000 workers, and Mississippi followed at 6.9 deaths per 100,000 workers.

Agriculture, ranching and forestry were among the most deadly work sectors, according to the state’s annual report, followed by mining and oil and natural gas extraction. Across all industries, highway crashes and vehicular accidents accounted for 67% of all occupational fatalities in 2023.

At face value, workplace fatalities can appear to be “random” from year to year, according to Wyoming OSHA Program Manager Christian Graham. It’s tempting, he said, to point to Wyoming’s often-hazardous driving conditions, or unregulated ranch work, or employees shirking safety protocols.

“There’s so many instances where sometimes these can be prevented if we just slow down and pay attention,” Graham said.

Yet, it’s difficult to derive from data what exactly is behind Wyoming’s worker fatality problem, Graham cautioned. The labor, safety and workforce regulatory world is full of reductive reports and databases that, individually, don’t reveal root causes or how to address them. To understand and effectively address what plagues workplace safety, Graham said, requires deep, ongoing analysis and interaction with employers and employees. Wyoming OSHA and the Wyoming Department of Workforce Services do have those conversations with both employers and employees, he said. The agencies also oversee multiple programs that go beyond inspections and enforcement to provide services such as safety training and voluntary consultations.

“One death is too many,” Graham said, adding that more resources are always welcome. “We do our best while we’re out there to present our programs, and we’re completing our inspections throughout the state.”

Though workplace inspections and training programs are vital, the state does not do enough to hold employers accountable, Kindred said. She bristles when people chalk up the state’s track record to vehicle accidents and on-the-job suicides and homicides — which are included in the state’s tally.

“We also have the highest rates of suicide in the nation, and that’s a workers’ issue,” Kindred said. “If they’re doing it on the job, these are deaths of despair because they’re at this job they hate that doesn’t pay enough and they can’t support their families.

“And if a lot of these [vehicle fatalities] are out-of-state truckers,” Kindred added, “we need to make sure they’re prepared. We need to be better neighbors. If people are sending their workers to Wyoming and they’re dying, that’s not the reputation we want.”

There’s always a desire to pin the blame on workers for taking short cuts or not following procedures without acknowledging the pressures they’re under and things they don’t have control over, like improperly maintained equipment or the right tools for the job, said Tyson Logan, a partner at the Spence Law Firm, which specializes in workers’ rights.

“We see it all the time,” Logan said. “Wyoming workers are going out to do their job and being killed because of corporate negligence or recklessness. And what we see again and again is that companies just aren’t making their workers’ safety a priority.”

Most employers provide proper training and equipment and encourage a culture of safety, Logan said, noting a slow cultural shift over decades.

“It’s daunting, though. The problem is it’s not every company or every job,” he said. “When the economy is not as strong, companies tend to take more risks. When there’s fewer people, there’s more expectations and trying to do more with less. That’s when people get hurt.”

There are myriad inherent on-the-job risks in Wyoming, including long commutes to remote locations and working around heavy equipment, said Rep. Lee Filer, a Republican from Cheyenne who owns a company that builds and operates data centers.

“Every bit of the equipment they’re running, none of it is forgiving,” Filer said. “If it’s a forklift or front-end loader, that’s thousands of pounds hitting you. So it doesn’t take much.”

Despite embracing safe workplace practices while serving in the military and as a union representative with the railroad, Filer admits he lost a fingertip to a saw blade due to his own recklessness.

“I did it myself,” he said. “But I do the best I can to make sure that my crew is safe. I always tell them, ‘Come let me know if you have a concern,’ because I don’t want anybody getting hurt. And I’ve been pretty successful with that.”

Too many workers, however, feel they’re under pressure and don’t speak up, he said. His biggest worry is worker fatigue and commuting to and from work.

“It could be mandatory overtime issues where people maybe work 12 hours, 16 hours, then have to drive home,” Filer said. “Wyoming is always going to have a bad rap on this because of our shift work. A lot of our industries — the coal mines and railroads — those places are 24/7 operations.”

Kristy Wardell, right, helps align a ramp onto an upper deck of a sheep-moving truck. She started the trucking business to help keep her family’s century-old wool growing business afloat. (Mike Koshmrl/WyoFile)

What’s being done about it?

Beginning in the 2000s, a spike in fatalities and injuries that coincided with a coalbed methane and natural gas drilling boom spurred advocates like the Wyoming Trial Lawyers Association, Wyoming AFL-CIO and the Equality State Policy Center to increase pressure on leaders in Cheyenne.

The response wasn’t immediate. But eventually, the state organized special hearings and there was a genuine statewide discussion about how to make workplaces safer, according to Shanor, who played a key advocacy role. Industries responded, too, forming the Wyoming Oil and Gas Industry Safety Alliance, the Wyoming Transportation Safety Coalition and a new safety training center in Casper.

There were even modest reforms — which were hard-fought, Shanor said — such as an annual cost-of-living adjustment and an increase in death benefits under the Wyoming Workers’ Compensation program. The Legislature in 2014 considered increasing fines and penalties for egregious safety violations to dissuade what some referred to as a “disposable worker” attitude among some employers in the region. The state even created an occupational epidemiologist position at Wyoming Workforce Services to not only analyze workplace fatality and injury data, but to coordinate information among multiple, siloed agencies that investigate worker fatalities to help identify strategies to do something about it.

The drive to finally address Wyoming’s workplace fatality epidemic, however, petered out, Shanor said.

The Wyoming Oil and Gas Industry Safety Alliance is no longer active, according to Wyoming OSHA, and the Wyoming Transportation Safety Coalition is trying to regain footing. The state recently reclassified the occupational epidemiologist post to an “OSHA compliance assistance position,” which means the state is no longer performing the deep analysis of root causes like it had in the past.

OSHA defended the changes as enhancing “our ability to support health and safety throughout the state by guiding rule and standard development, conducting outreach, and being an accessible resource.”

But Shanor, the workforce safety advocate, doesn’t see it that way.

“That’s a huge loss,” she said.

“I just think we lack leadership,” she added. “I worry that maybe we let them off the hook after COVID.”

Kindred, of the AFL-CIO, was more blunt.

“[Wyoming leaders] like to talk about our work ethic and how we love our workers; We get the job done and we don’t complain,” Kindred said. “But when it comes time to put our policies and our efforts where our mouth is, we just want workers to be our mascot. We don’t really want to support them in any way.”

It’s disheartening, Kindred added, because Wyoming really is the place where people will pull over to help a stranger broken down on the side of the road. “That’s why our continued inaction on workplace safety is so jarring. It contradicts our fundamental values.”

Filer, who served on the Labor, Health and Social Services Committee during his first stint in the House of Representatives from 2013 to 2014, said he’s seen a shift in the Legislature from solving Wyoming problems to adhering to ideology.

“Worker safety, to me, is not an ideology or political position,” Filer said. “It’s something that everybody can probably agree on — that everybody wants to come home to their family when they get off work.”

Filer said he’s in favor of asking for more detailed reports, analysis and ideas from Wyoming Workforce Services and Wyoming OSHA, and generally prioritizing the workplace fatality epidemic at the Legislature. While he’s adamantly opposed to regulations, some are necessary, like “OSHA laws,” Filer said. “There’s a reason those [laws] are on the books. It’s because they were written in blood.”

Transportation, Highways and Military Affairs Committee Co-Chair Rep. Landon Brown, a Republican from Cheyenne, said he wants the panel to take up the worker transportation safety issue this year.

Labor Committee co-chairs Sen. Eric Barlow of Gillette and Rep. Rachel Rodriguez-Williams of Cody, both Republicans, did not respond to WyoFile’s inquiry about whether the committee will take on the issue.

Among the committee’s proposed topics this year, however, is to consider lowering — again — what employers pay into the workers’ compensation program to “promote a more business-friendly environment” and “random” drug and alcohol testing of employees at state-funded institutions.

“It is time to re-energize this conversation and return worker safety to the forefront where it belongs,” Shanor said. “This silence is not just troubling; it is unacceptable.”

To contact Wyoming OSHA regarding workplace safety concerns, call 307-777-7786.

If you or someone you know is having suicidal thoughts, call or text the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline at 988.

WyoFile is an independent nonprofit news organization focused on Wyoming people, places and policy.